After record period of ship removals, younger, more efficient fleets remain

Six Fantasy-class Carnival ships. Three vessels from Royal Caribbean’s now-defunct Pullmantur line. Holland America Line’s former Westerdam.

These ships were among 38 vessels sold to shipbreaking yards since the pandemic began, representing the largest exodus of cruise ships in history. The result? A worldwide cruise fleet of larger, younger and more efficient ships.

Last year alone, cruise lines sent a record-setting 18 ships to scrapyards, according to the Cruise Ship Secondhand Market Report by Cruise Industry News. By comparison, the industry typically scrapped two or three ships a year before the pandemic, said Monty Mathisen, managing editor of Cruise Industry News.

The pandemic pause in operations sped up retirements of older ships that were expensive to keep up, he said.

“Just sitting on it costs a lot of money. It’s not like a car you can just leave somewhere and maybe change your battery a year later and it will start,” Mathisen said. “There’s not a huge list of buyers for 30- to 40-year-old cruise ships, either.”

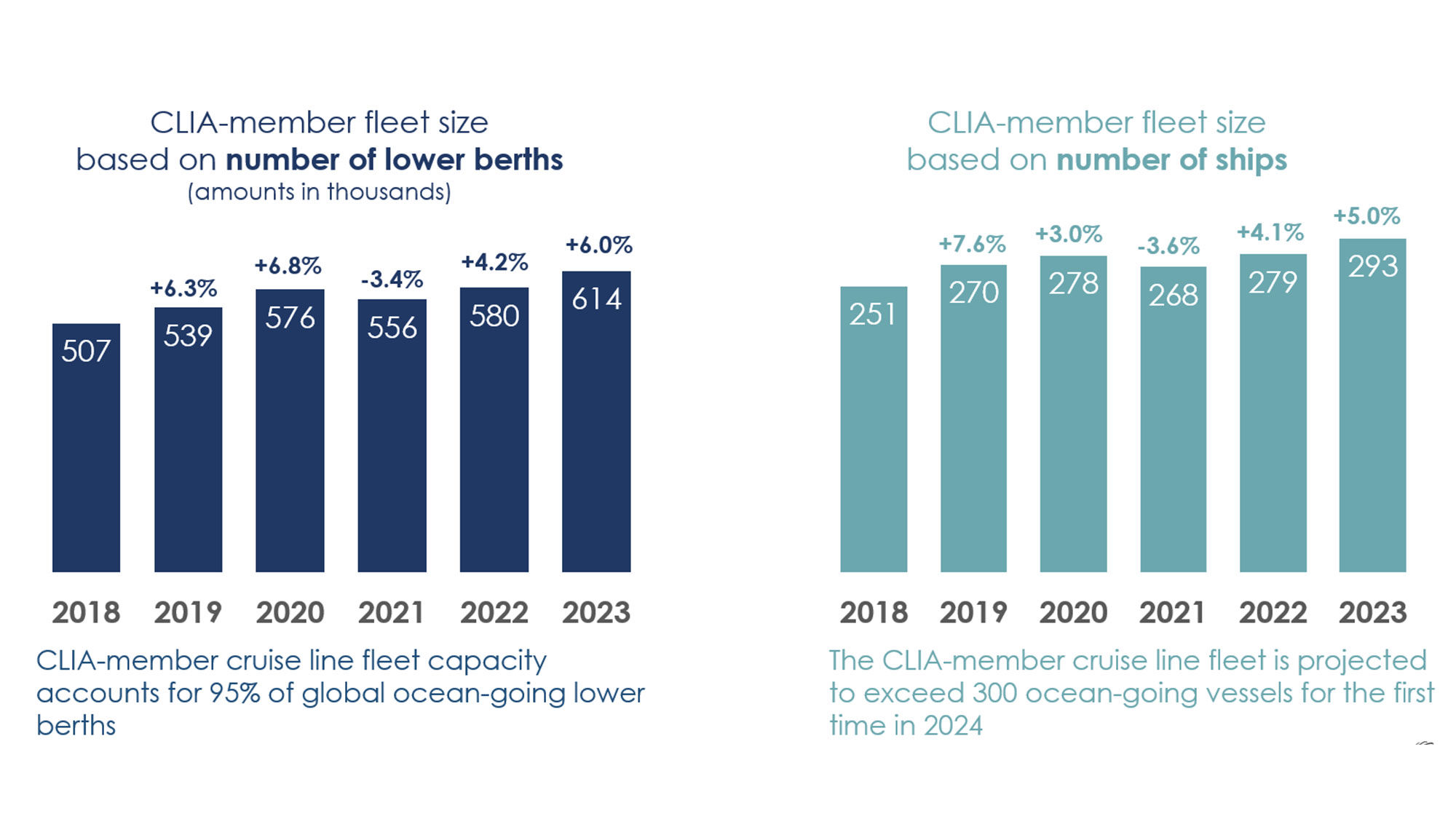

Despite the boost in scrapping, cruise lines have kept growing. The number of CLIA-member ships has grown to 293 this year from 270 prepandemic. Lower berths grew, too. Members now have 614,000 lower berths, compared to 539,000 in 2019.

“The fleet isn’t shrinking. It’s just getting younger,” said Brian Salerno, senior vice president of global maritime policy for CLIA.

The average age of the CLIA membership’s fleets is now about 14 years old, he said, whereas it was around 15.5 years old before the pandemic.

While the halt in operations during the pandemic put financial pressure on cruise lines, it also squeezed the ship resale market, said Peter Shaerf, managing director of AMA Capital Partners, an investment banking firm focused on the maritime sector.

No market for old ships

“In previous times, they might have sold those to the second-tier buyers, who don’t compete with them. Those people were not there,” Shaerf said, noting those lines were also saddled with huge debt and no business during the pause in operations. “If you can’t find a buyer, you scrap it.”

Carnival Corp. brands sold off the most ships during the pandemic, including six of Carnival Cruise Line’s Fantasy-class vessels.

The Fantasy-class ships were each 30 years old or younger, generally considered young to head to the graveyard. But that is where they went, contributing to an overall drop in the age of scrapped ships. From 2017 to 2019, the average age of a scrapped ship was 43. During the pandemic, that average age dropped to 37, according to Cruise Industry News. Carnival sister brand Costa Cruises’ Costa Victoria was also scrapped during the pandemic — at only 23 years old.

Meanwhile, some smaller cruise lines downsized or collapsed. For example, Bahamas Paradise Cruise Line sold one of its two ships for scrap and rebranded to the single-ship Margaritaville at Sea. Pullmantur, a Spanish brand jointly owned by Royal Caribbean Group that folded in 2020, scrapped its three ships, two former Royal Caribbean vessels and one from Celebrity Cruises.

While there are still more ships to be bought, “there are very few active, serious, capable buyers in all levels of ships,” Shaerf said. “I think there are very few cash-ready buyers.”

The price of steel also made scrapping ships more attractive in recent years, said Peter Knego, a cruise ship historian.

“Those ships went last year in such mass quantities because steel prices were really high,” he said. “So anything that was in layup was in demand, because there was demand.”

The price of steel has risen since the beginning of the pandemic, said Rye Druzin, associate editor of steel, pipe and tube for Argus Media, which tracks steel prices.

The price of heavy metal scrap is now 40% higher than it was in 2019, Druzin said, and hot rolled coil, another type of steel that can be stripped from cruise ships, has almost tripled in price since 2019.

“Cruise ships consume large amounts of flat steel and plate products, and while prices of both have declined in the last year, they remain at elevated levels compared to their historical averages,” he said.

The ‘greening’ of cruise fleets

Meanwhile, the retirement of older ships and the steady introduction of new vessels are making fleets younger and helping the industry work toward meeting its environmental sustainability goal of net-zero carbon cruising by 2050.

The 44 ships on order over the next five years will be more efficient and use newer technologies, said CLIA’s Salerno. For instance, new ships are often built with the capability to burn more than one type of fuel and will be able to utilize cleaner fuel sources once they become more readily available.

“There’s really a push to become more fuel efficient and to make use of newer types of fuels,” Salerno said. “Decarbonization and reducing greenhouse gas is becoming more energy efficient generally. So, the newer ships really aid in that. Not that the problem is completely solved, but it helps move it in the right direction.”

Source: Read Full Article