How This Michigan Town Became "Black Las Vegas"

“When we got to Idlewild and saw the blinking light to turn into Idlewild Beach, it was like coming back to family,” says Carlean Gill. “People looked out for one another and they laughed together. It was really just like a homecoming.”

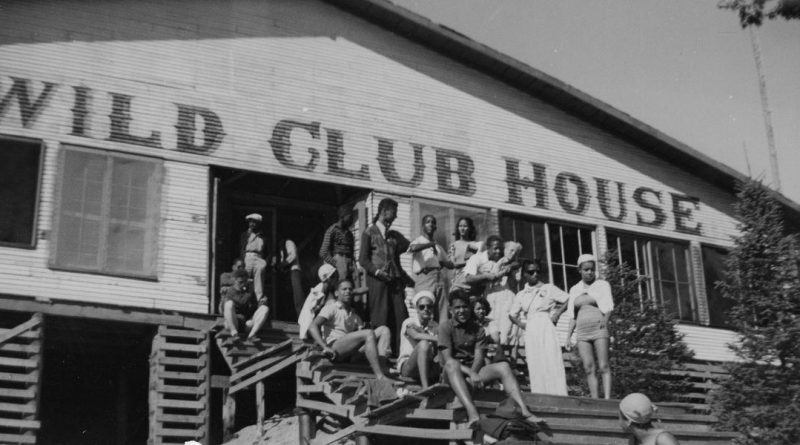

Gill, 82, is reminiscing about the Black lakeside resort town in Michigan where she worked as a showgirl in the 1950s and 60s. In its heyday, Idlewild was the premier destination for Black travelers, a Black Las Vegas, with rising music stars and comedians, right in the middle of rural Yates Township.

Load Error

Every weekend, visitors from Detroit, Saginaw, and Flint—and across the country—checked into beach cottages, hotels and more than 50 motels–most of which were Black-owned. During the day, they swam, sunbathed, sailed, and fished. At night, you could have a casual drink at Rosanna’s Tavern, hit the roller rink or dress for dinner and a show at the Purple Palace, the El-Morocco, Flamingo or the Paradise Club.

Many considered Arthur Braggs’ Paradise Club the premier venue, where you could see Aretha Franklin, Jackie Wilson, B.B. King, Della Reese or the Four Tops for just a few dollars. And if you were lucky, you might be able to share a glass of Cognac or Coca-Cola with them after the show. There were scores of motels, restaurants, and even a little gambling if you were so inclined. “They even had a cliche: ‘what happens in Idlewild stays in Idlewild,’” says Ronald Stephens, PhD, a Purdue University professor of African American studies who’s written two books on the community.

Stories about the glitz and glamour of 1950s Idlewild are seductive, even to academics.”When I first learned about it, I had romanticized its history because of the entertainers, and not the entrepreneurs,” says Stephens. But when he dug deeper, he learned the long history and the deeper significance of the community.

White developers founded Idlewild in 1915, during Jim Crow segregation, and invited well-to-do Black people from the Midwest to come visit, similar to timeshare pitches today. “You have some very well-to-do African Americans who were professionals who were beginning to experience the promise of mobility,” says Stephens. “And mobility meant freedom.” But there were few safe places to go. Just the name Idlewild is evocative of an undiscovered place where you can relax and explore.

Idlewild quickly attracted affluent Black lawyers, doctors, and educators. Ads in the Chicago Defender and Cleveland Plain Dealer advertised the chance to own a piece of this Black Eden. Daniel Hale Williams, a Black Chicago surgeon who performed the world’s first successful heart surgery, owned property there. So did Charles Waddell Chestnutt, a prominent novelist and attorney, and Madame C.J. Walker, who became America’s first self-made millionaire with her wonderful hair grower. W.E.B. DuBois owned a home there, and is seen enjoying the water and walking in the woods in historic photos.

Victor Green featured Idlewild in his very first Negro Motorist Green Guide, the directory of safe destinations for Black travelers, when it launched in 1936. After World War II, Idlewild’s clientele expanded to returning veterans, and people working in booming post war industries. “Cab drivers, auto workers, numbers men and women, they wanted vacation life and relaxation,” says Stephens. “It was almost like an oasis. They weren’t allowed to go to other places. That was a place they felt secure and safe, where they could in a sense let their hair down.”

There was some tension between the several hundred year-round residents and the vacationers and the businesses that catered to visitors. But everyone enjoyed the shows at the Paradise Club. The chefs, bartenders and waitstaff were cherry picked from the best places across the Midwest. “Everybody that came in was a specialist in what they did,” Gill says. “There weren’t people that didn’t take pride.”

During a typical show, Lottie the Body would do exotic dances, and Jackie Wilson or Etta James might sing. “They really honed and learned their craft before Motown came into existence,” says Gill. The Bragettes were a chorus line that did can-can style dancing with high kicks with musical accompaniment by a 16-piece band. Gill was one of the four showgirls called Fiesta Dolls. It was all very exciting for a former beauty queen from Ferndale, Michigan.

During the offseason, Braggs took his Idlewild Revue on the road with a 36 person troupe that included a costumer and a choreographer. They worked the Chitlin Circuit, a network of Black clubs including the Apollo in New York and locations in Chicago, Cleveland, and Boston, but they went into white clubs too, and helped inspire more people to visit Idlewild.

Braggs lobbied for residents and town businesses to invest in infrastructure, but his ideas met resistance. “Some in the community felt they no longer needed an Arthur Braggs,” says Stephens. “They said Idlewild is going to be Idlewild with or without you.”

Idlewild’s golden era ended swiftly, with the passage of the Civil Right Act of 1964. Black people could legally go other places, and interest in Idlewild waned. Braggs’ revue stopped performing that year, and he bought a horse farm.

Today, Idlewild lives on as a romantic notion celebrated in the eponymous 2006 musical film, featuring music (and acting) by OutKast. There are still families who summer at the lake, as they have for generations, and the Idlewilders across the Midwest share pictures and memories online. But Idlewild is also attracting a new generation.

Replay Video

SETTINGS

OFF

HD

HQ

SD

LO

Entrepreneur Denise Bellamy didn’t visit Idlewild until the 1990s. On an early visit, she saw a themed party, with people in costumes having a good time under colorful tents. They were members of the five National Idlewilders clubs that dot the Midwest. “I wanted to be part of that so bad, and I was,” Bellamy says.

Bellamy opened a convenience store that sold everything from wine to hair extensions, and moved to Idlewild. There, she became friends with town pillar Mary Ellen Wilson, whose family name is on many streets, and inherited Wilson’s lakefront home. “She taught me how to drive a boat,” says Bellamy. “She was a jewel.” Bellamy sold her business a few years ago, but she’s still working to preserve quality of life for lakefront homeowners and encouraging investment in the community. “It’s still not Martha’s Vineyard, but it’s a place people of color can go and it’s a safe environment in rural America,” says Bellamy.

Tinisha Brugnone, a Detroit filmmaker, had never visited Idlewild before 2019. But on a music festival weekend, she fell in love with the place, and made a short documentary film. Her small screening of Afrocentric films ballooned, and she ended up launching the Idlewild International Film Festival in 2019. The outdoor festival attracted films from Korea and Italy, and 300 people who shared in the Woodstock vibe. As COVID-19 cases subside, she hopes to reprise it in 2021. “I’d like it to be the Black Sundance,” she says. “A lot of folks there like to live in the past,” says Brugnone. “What is really intriguing is what it can be now.”

Many years after the end of legal segregation, Stephens says there’s a compelling reason why two Idlewild television projects in the works, and why Idlewild is just as enchanting as Wakanda.

“If you’re African American, whether you are in your car on a Wednesday in Atlanta, Georgia you can get shot and killed or whether you’re jogging in a white neighborhood, you can get shot and killed,” Stephens says. “I think more African Americans are realizing there’s a need for a return to the places that we once had.”

This story is part of a continuing series on historically significant Black neighborhoods in the U.S.

Follow House Beautiful on Instagram.

Maria C. Hunt is a journalist based in Oakland, where she writes about design, food, wine, and wellness. Follow her on instagram @thebubblygirl.

Source: Read Full Article