Rediscovering Japan

Outside Tokyo’s Hotel Groove Shinjuku, where I was ensconced on the 36th floor, is Toho Cinemas, where a huge replica of Godzilla looks like it’s trying to gobble up Harrison Ford in the heart of the Kabukicho entertainment district.

The sign advertising “Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny,” the latest in that movie series, declares, “To the final challenge that will change our destiny.”

Other than thinking how apt that statement is, in light of the pandemic challenge that Japan tourism has been through, I’ll also have you know that as a media franchise, “Godzilla” is way older than “Indiana Jones.”

The fictional monster made its debut in 1954, in Ishiro Honda’s film, as a prehistoric creature empowered by nuclear radiation, while Indiana Jones made his first outing in “Raiders of the Lost Ark” in 1981. (Still, I must say, that while Indy has needed the help of AI and CGI to de-age him in his latest romp, Godzilla looks like he’s hardly aged at all!)

Godzilla is only one of the many Japanese media franchises that’s captured the world’s imagination. In fact, according to Tokyo-based economist Jesper Koll, speaking at Web in Travel’s WiT Japan & North Asia conference in July, of the 25 highest-grossing media franchises of all time, Japan owns 10, including the top two: “Pokemon” and “Hello Kitty.”

More kids in Asia know Pokemon and Hello Kitty than they do Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck, said Koll.

In fact, if you ask Scoot, Singapore Airlines’ low-cost subsidiary airline, how popular Pokemon is, they’ll tell you that their Pikachu-emblazoned jet, launched in 2022 to celebrate its 10th anniversary, has made the airline the darling of Gen Z and millennials in Asia. That aircraft is always the first to be filled, according to the airline, which has seen robust recovery in inbound traffic to Japan.

Koll was speaking to the soft power of Japan, saying that even as general perceptions paint the country as an aging and declining power, things couldn’t be further from the truth on the ground. In fact, he says the new Japan that has emerged since the pandemic is a “first-class power, with rich companies and rich consumers, a new middle class, a lifestyle superpower and a bastion of policy stability.”

He shared these numbers from the Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report 2020:

Unlike many Western countries, it’s not a “winner takes all” in Japan when it comes to household wealth: Of the total wealth of $26.9 trillion, 49.5% belongs to the top 10%, 18.2% to the top 1%. Compare that with the U.S., where total wealth is $126.3 trillion, with 75.6% of it in the top 10% and 35.3% in the top 1%. In Japan, the salaryman rules over the superstar CEO.

As for the aging and declining population, Koll said a new middle class is emerging in Japan for the first time in 20 years, growing from 32.8 million in June 2014 to 36.6 million this past April.

What’s also unusual about Japan, he said, is “there are no superstars” when it comes to companies.

Unlike the U.S., where revenue share is dominated by a few top companies, Japan is a “red ocean of many companies,” which is why foreign companies find it so challenging to enter and penetrate the market.

His talk was enlightening in that it made me look at Japan with new eyes and made me more aware of the subtleties and nuances that make Japan such a fascinating destination for travelers. Perhaps it was also time away from one of my favorite places on Earth that’s allowed me to gain new perspectives on a familiar place.

Change is brewing

On the surface, it felt like nothing had changed on this return visit to Tokyo, my first since 2019. I had landed at Haneda Airport on a Sunday evening, and by the time I got to Kabukicho it was well past midnight, but the city’s most famous entertainment district was heaving with energy. It felt like a full frontal assault on the senses, to be right back in the heart of it, amid the crowds, the noise, the convenience stores and the neon lights.

In the square, groups of Japanese kids were hanging out — listening to their music, dancing, skateboarding, doing whatever-makes-their-groove — while a few security officers looked on dutifully. Kabukicho is as lit up as Times Square; only the images are different. Here you are more likely to see highly Photoshopped images of young girls with big eyes and pretty boys with dimpled smiles than news bulletins and stock prices.

But change is brewing in this slice of Tokyo.

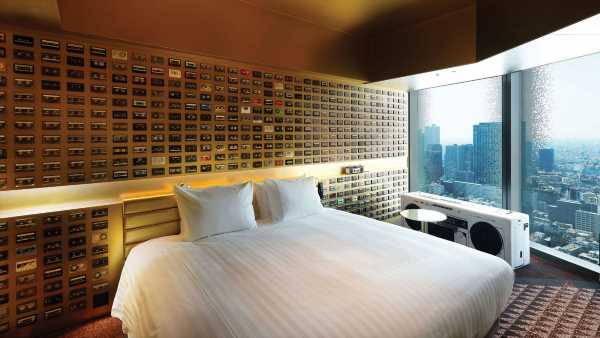

The Hotel Groove Shinjuku as well as the Bellustar Tokyo are located within the new Tokyu Kabukicho Tower, whose design by renowned architect Yuko Nagayama has made it the city’s newest attraction, and more significantly its development is part of a bigger strategy to transform the image of the Kabukicho district from a red-light zone to more hip, artsy and eclectic.

Nick Nishikawa, general manager of the two hotels, says the idea is to slowly change the image of the district so that corporate clients will feel as at home here as leisure guests.

The Hotel Groove Shinjuku, a Parkroyal Hotel, has an artsy vibe — it has themed rooms that double as art installations — and the majority of guests are young and Asian. The more upscale Bellustar Tokyo, a Pan Pacific Hotel, is aimed at the corporate traveler and the meetings market.

The staff who checked me in at the Hotel Groove was from China — and that’s one noticeable difference with this visit to Tokyo. I don’t know if it’s related to the pandemic, but I came across more foreign service workers this time, such as Chinese Uber drivers who decided to stay on after their studies. One of them, from Shanghai, told me he’s so happy to be in Tokyo “because I can get away from my parents.” Kids are the same everywhere, really. I also met older Japanese taxi drivers, who were more than happy to speak English with me.

Japan has always struggled with diversity on all levels — not just gender but nationalities. It’s always seen to be very monoculture and not easy for foreign talent to enter and remain in the workforce. It has also struggled with dispersal of tourism beyond the main cities of Tokyo, Osaka and Kyoto; prepandemic, over-tourism was a key lament of Kyoto.

Again, change is brewing on these fronts.

At WiT Japan & North Asia, we heard from Pasona Group, Japan’s leading executive recruitment firm, which took the bold step of moving core functions of its Tokyo headquarters to the remote Awaji Island in Hyogo Prefecture, near Kobe, during the pandemic and relocated roughly 1,200 employees.

It did this to force diversity in its workforce and to bring more people to the rural areas, said general manager Riho Kato. “We have 100 people from 30 to 40 countries working with us: from young to old, disabled, from different cultures and backgrounds — artists, athletes.”

Asked if it faced challenges recruiting people in Awaji, Kato said, “Japan is Japan; it doesn’t matter if it’s a rural area. In fact, they prefer it sometimes. We want to gather diverse talent; there are many professionals who after retirement have a lot to contribute and can bring different views to hospitality, for example.”

New ideas in tourism

When I asked Japan Travel Bureau president Eijiro Yamakita if he would ever consider such a move of headquarters to a rural area, he said it wasn’t an impossibility, which is solid proof that the pandemic has definitely prompted new thinking on everyone’s part, including that 111-year-old company.

Trying to play its part in dispersal of tourism, too, is Airbnb, which has donated 150 million yen (roughly $1 million) to the Japan Kominka Association that addresses succession of Japanese-original architecture and local economy revitalization through renovation of old Japanese-style houses. The association plans to support up to 5 million yen each (that’s about $36,000 U.S.) for renovation of 30 houses nationwide, and those houses will eventually be listed as Historical Homes on Airbnb’s platform.

Then you have MGM Resorts, which has finally gotten the go-ahead to build its $10 billion Integrated Resort in Osaka after nearly a decade of waiting for approval. MGM’s chief of staff for Japan, Jiro Kawakami, speaking at WiT Japan & North Asia, shared plans for the resort, which MGM expects to be its most profitable when it opens in 2029.

“Most people think Las Vegas is a big gaming market, but it’s only $8 billion in annual gaming revenues,” Kawakami said. “Macau is $35 billion (pre-Covid). Japan’s market is huge. It’s a strong destination with 18 Unesco World Heritage sites. There are so many things to do outside the Integrated Resort — if you look at what Marina Bay Sands Singapore has achieved, with such a small market and only one Unesco World Heritage attraction, it’s unbelievable.”

So other than the 2,500 rooms across two hotel towers and its roughly 140,000 square feet of meetings space and 215,000 square feet of exhibition space, one key feature of the resort will be a unique facility that will act as a large-scale tourism concierge to promote travel to other parts of Japan, including Kyoto, Nara and the greater Kansai area.

Asked to imagine what this tourist-sending facility/concierge could look like, Kawakami said, “I would love to see customers being able to utilize AI to create personalized, customized tours so they won’t need a lot of encounters with humans. Maybe lots of terminals where people can ask, ‘I want to eat unagi in Nara, and I want counter seating.’ So in that regard, there is a thought to place more emphasis on AI-created content.”

To assist Kawakami to visualize the facility, we created an image with the Mid-journey AI program, using his word prompts. I guess you’ll have to check back here in six years to see if AI got it right.

In the meantime, I wouldn’t mind some AI or CGI to de-age me. Godzilla, I am not.

Source: Read Full Article