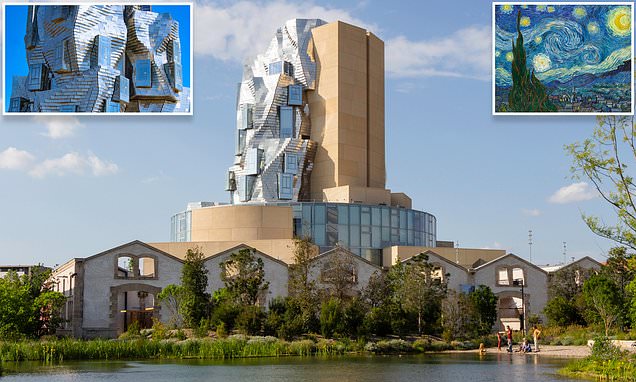

The dazzling Frank Gehry building inspired by Van Gogh's Starry Night

Starry sight: Van Gogh adored Arles. And now a dazzling art centre inspired by his most famous piece of work is raising the French city’s profile

- Ten-storey ‘Luma’ is designed by Frank Gehry, famous for his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao

- It’s made of 11,000 twisted stainless steel panels, glass and concrete, dominating a huge ‘creative campus’

- The inside, with its double helix staircase and grand exhibition spaces, is equally spectacular, says Anwer Bati

Vincent Van Gogh loved the light in Provence so much that he moved to the southern French city of Arles in 1888 for one of the key years of his short life. So how fitting that a new building, which dazzlingly reflects that light, has made Arles a major centre of contemporary art.

Called Luma, it is designed by Frank Gehry, famous for his Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, who took inspiration from Van Gogh’s famous painting The Starry Night.

At the long-awaited opening last summer, 600 art and architecture bigwigs, including such names as Norman Foster, tucked in to Michelin-starred bull tataki, heralded by a trumpet fanfare, and oozed admiration for this brainchild, commissioned by Hoffmann-La Roche pharmaceutical heir Maja Hoffmann, who was brought up in the area.

Luma, above, in Arles is designed by Frank Gehry, who took inspiration from Van Gogh’s famous painting The Starry Night

And it’s quite a sight: a ten-storey tower made of 11,000 twisted stainless steel panels, glass and concrete dominating a huge £150 million ‘creative campus’ on the site of a former railway yard.

The inside, with its double helix staircase, and grand exhibition spaces for regularly changing art shows, is equally spectacular. And the view from the top of Arles and the surrounding Camargue countryside is worth the visit alone.

Gehry says he was influenced by both Van Gogh and the city’s UNESCO-listed Roman heritage in his design, but I’m taken aback by one unlikely homage to the area: the wall panels lining the lift lobbies are made using local salt crystals, and acoustic panels in the bar were created using biomatter from Van Gogh’s beloved sunflowers.

The creation of Luma has led to smaller art galleries flourishing in its wake.

One of them is Galerie Huit, in a 17th-century mansion restored by Brit Julia de Bierre, which doubles as the most stylish B&B in town.

‘It’s amazing,’ says Julia, who specialises in avant-garde photography. ‘So many creative people are settling here. There used to be five galleries, now there are 50.’

And thanks to the new influx of art lovers, local restaurants have raised their game, with some excellent choices including the family-run Le Criquet; the new Camargue Social Club, a wine bar serving delicious, locally sourced tapas; and L’Arlatan in Hôtel à Arles, now owned by Maja Hoffmann.

Yet art in Arles is inevitably overshadowed by Van Gogh, who, in a burst of creativity, produced dozens of his best-known works in the city, including Café Terrace At Night.

‘It often seems to me that the night is much more alive and richly coloured than the day,’ he wrote to his brother Theo.

Luma is a ten-storey tower made of 11,000 twisted stainless steel panels, glass and concrete

TRAVEL FACTS

Ryanair Stansted to Marseille return flights from £34 (ryanair.com). Trains from Marseille to Arles take around an hour. Double rooms at the hotel Jules César from £156 per night B&B (hotel-julescesar.fr). Entry to Luma (luma.org) is free, but you must book. For more information: arlestourisme.com/e.

The café that inspired the painting still exists — in the focal Place du Forum. But my guide, Elodie, explains that, although the café is now coloured yellow to resemble Van Gogh’s depiction, it was formerly white — but the colour was distorted by the gas street lighting.

Arles was where the artist famously cut off his ear, and near by is the 16th-century hospital where he was later taken. Built around a courtyard, which Van Gogh painted, it is now the Espace Van Gogh, a lively cultural centre.

But surprisingly, there is only one of his works on show in the city — at the Fondation Vincent Van Gogh, a gallery established by Maja’s father, Luc Hoffmann, which holds retrospectives of major contemporary artists and temporarily borrows Van Goghs from other collections.

My hotel, the Jules César, just down the road from Luma, is ideally placed to explore the city. Built around the cloisters of a 17th-century former Carmelite convent, it was recently revamped by local boy, fashion designer Christian Lacroix.

It is on the Boulevard des Lices, Arles’s main street, which on Saturdays is the venue for the biggest market in Provence, stretching for over a mile.

In a carnival atmosphere, stalls heave with everything from plump, glistening vegetables to hair trimmers.

Arles was a key Roman city (vividly evoked in the impressive Musée de l’Arles Antique) and just across the Boulevard des Lices is the ancient theatre, built in the reign of Augustus.

It once held 7,000 people and, although its stones were plundered to build local homes over the centuries, it still comes to life for performances — including, appropriately, an annual film festival of sword-and-sandal epics.

Near by is the remarkably well-preserved arena where gladiators once fought. It was one of the biggest in the Roman world and became a mini-town, containing hundreds of houses, from after the fall of Rome until as recently as the 19th century.

Van Gogh painted the crowd at a bullfight in the arena in 1888, and bullfighting still takes place there during festivals — both to the death and in a local version, more like bull-bothering, when men dressed in white run to dodge them, not always successfully.

Festivals find women wearing the traditional Arlésienne costume of long dresses and lace shawls, which Van Gogh praised for ‘the grand lines . . . vivid in colour and admirably carried’. Rather less demurely, Camargue cowboys, or guardians, can be seen riding through town on their famous white-grey horses, like something out of the Wild West.

Arles is like that: a mixture of the genuinely ancient, the traditional — and the contemporary.

Source: Read Full Article