Dating issues and no takeouts: The reality of life on a tiny island

‘Amazon parcels arrive by ferry and there was the time a Cuban turned up on a raft’: Man who lives on tiny Pigeon Key island at the southern tip of the U.S reveals what life is like there

- Pigeon Key island is part of the tropical Florida Keys archipelago

- Kelly McKinnon spent over a year on it with a cat and a rescue duck for company

- ‘When the pandemic hit, this was the best place in the world to be,’ he says

‘For quite some time it was just me living out here… me, the cat and a [rescue] duck, for a little over a year,’ says Kelly McKinnon, who has spent the past 14 years living on Pigeon Key, a five-acre island off the coast of Florida.

Fortunately, he ‘doesn’t mind the isolation’.

Plus, he reveals that life there has its interesting moments – his Amazon parcels arrive on ferries, the fishing is epic and a man once arrived from Cuba on a raft – and the lockdown didn’t really affect him: ‘When the pandemic hit, this was the best place in the world to be.’

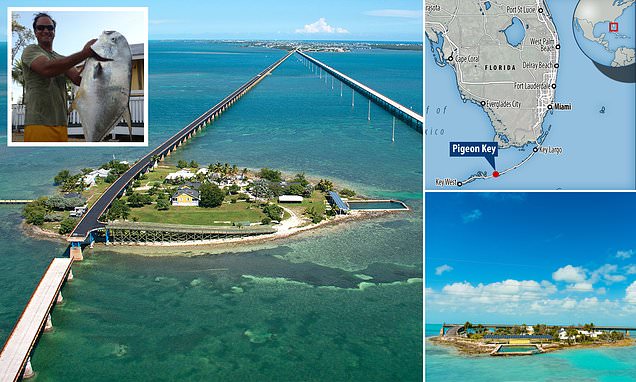

Kelly McKinnon has spent the past 14 years living on Pigeon Key, pictured, off the coast of Florida. The nearest shop is around two-and-a-half miles away to the west on neighbouring Knights Key, reached via the Old Seven Mile Bridge, which runs right over the island but is disconnected to the east

‘It’s not a place where if you forget the eggs you’re going to go back. You just do without,’ says Kelly McKinnon (pictured), one of only four permanent residents on Pigeon Key

On the downside, island life has wreaked havoc with his love life – ‘the island has eaten up a few girlfriends’, he admits.

McKinnon’s minuscule island home is part of the Florida Keys archipelago that stretches to America’s most southern point and is connected to the Keys in one direction only – to the west, by way of the historic Old Seven Mile Bridge, which runs right over the island but is disconnected to the east.

One of only four permanent residents, he is executive director of the Pigeon Key Foundation, a non-profit organisation that works to protect the area’s culture and history. And with the other three residents employed by McKinnon, he might best be described as ‘the boss of the island’.

The Michigan-born islander lives by himself in a small wooden house built in 1916 – one of just eight buildings on the island – and has got what he describes as a ‘pretty good view’.

The porch has unspoilt views of crystal clear turquoise water and looks out over a lawn where herons fish from the garden bench, framed by palm trees.

The nearest shop is around two-and-a-half miles away on neighbouring Knights Key and with access only via boat or the Old Seven Mile Bridge – open to walkers, cyclists and emergency vehicles only – the islanders ‘don’t leave too often’ and need to plan their meals carefully.

‘It’s not a place where if you forget the eggs you’re going to go back. You just do without,’ McKinnon says.

Asked if he’s able to use Uber Eats to stock up on food and McKinnon laughs heartily.

He says: ‘We don’t get Uber Eats, but sometimes the ferry that comes out will bring our Amazon packages to us.’

For McKinnon, the idea of getting a home delivery is so alien that when he visits friends in other parts of the world, the first thing he will do is order food. ‘We order a whole bunch of stuff to the door because it’s such a novelty,’ he says.

The keen fisherman reveals that he gets a lot of his food using his rod, taking his boat out to catch lobster, tuna, hogfish, permit fish and swordfish.

This drone photo shows the Old Seven Mile Bridge just before its big relaunch in January, 2022

A keen fisherman, Kelly McKinnon and his girlfriend, Ananda Williams (pictured with Kelly above left), often take a boat out to catch lobster and fish. ‘We’re able to source a lot of stuff right here,’ says McKinnon, who enjoys being self-sufficient. ‘If the bridge blew over tomorrow we could get by.’ He’s pictured on the right with a permit fish, a game fish native to the western Atlantic Ocean

‘We’re able to source a lot of stuff right here,’ says McKinnon, who enjoys being self-sufficient. ‘If the bridge blew over tomorrow we could get by.’

Living off the land on a tropical island might sound like a dream, but as McKinnon has discovered, it’s not for everyone.

‘I mean, I really like it here, but the previous girlfriends haven’t always been that excited about being on the island and being isolated,’ he says.

His current girlfriend, Ananda Williams, is a coral reef research biologist and lives in the city of Marathon, which is strung out along the keys to the west and takes about 20 minutes to reach by bicycle along the Old Seven Mile Bridge. ‘She’s underwater most days and it seems to fit her lifestyle,’ says McKinnon, happy to have found someone who isn’t fazed by a solitary life.

‘I mean, I really like it here, but the previous girlfriends haven’t always been that excited about being on the island and being isolated,’ McKinnon (pictured above) admits

Pigeon Key is part of the Florida Keys archipelago that stretches to America’s most southern point

This man arrived at Pigeon Key from Havana in 2016, using a small raft

However, despite the slow pace, the island has a way of throwing up the unexpected.

McKinnon recalls the bizarre day in 2016 when a man arrived at the island having paddled over from Havana.

He says: ‘One day we saw a gentleman running on a piece of the old bridge. Then he jumped in the water and swam up to the island. He had arrived using a small Styrofoam raft and claimed he had jumped in at Havana harbour.

‘We said hello and got him some water. I think he was allowed to stay.

‘It was an interesting day.’

Unreliable plumbing, we learn, can also disrupt McKinnon’s schedule.

The sewerage system is the main culprit. Being cut off from the mainland means waste cannot be pumped away, and when things go wrong it’s McKinnon that has to deal with it. ‘You’re literally working in s*** every now and then, so that’s not too glamorous,’ he says.

McKinnon says: ‘We don’t get Uber Eats, but sometimes the ferry that comes out will bring our Amazon packages to us.’ Pictured is one of the houses on Pigeon Key

When the job needs doing, it’s so atrocious that ‘I don’t even feel right about pulling rank and saying “hey – the boss isn’t doing this one”‘, he adds with a shudder.

The sleepy island has also seen some strange goings-on come nightfall. Aside from the twinkling phosphorescent glowworms that light up the ocean (McKinnon says it’s a spectacle not to be missed), some residents claim to have seen ghosts.

People who’ve stayed on the island say they’ve seen ghosts in windows of houses, heard spectral trains going by in the distance or felt a heavy weight on their chests at night.

‘I’ve never experienced any of these things. I don’t really want to,’ McKinnon says. ‘If there are ghosts out here hopefully they know I’m doing my best to take care of the place and keep the history and cultural aspects going.’

For McKinnon, the ghost sightings might be down to people’s wild imaginations, sparked by the island’s fascinating history.

In the early 1900s, it was the work camp of the 400 men who built what’s now the Old Seven Mile Bridge.

The bridge – originally called Knights Key-Pigeon Key-Moser Channel-Pacet Channel Bridge – used to carry steam trains and was made to the exacting standards of Henry Flagler, a railroad magnate who kept a close eye on his workforce. He was teetotal, and didn’t believe that drinking was conducive to hard work.

When it was built in 1912, the bridge over Pigeon Key was used to carry trains, as this undated photograph shows. The bridge’s original name was the Knights Key-Pigeon Key-Moser Channel-Pacet Channel Bridge

McKinnon says: ‘The reality of it is, it probably wasn’t a very nice place to work. Four hundred guys on a small island. No deodorant, limited fresh water, no women, no booze, no gambling.’

It’s these visceral details, together with the old Florida charm of the place, that McKinnon wants to preserve.

The Pigeon Key Foundation looks to bring the island’s history to life with tours and exhibitions, and they receive well over 200 visitors a day. That number is only set to increase following the $44million renovation of the Old Seven Mile Bridge earlier this year.

‘We’re not looking to turn Pigeon Key into Disney,’ McKinnon says. ‘It’s an unbelievably expensive environment to maintain because everything is 100 years old, made out of wood and in one of the harshest environments you can imagine.

‘We want to keep the vibe without ruining it for everybody – and me! I live out here, so 500 people in the yard a day seems like more than enough.’

McKinnon is pictured here on the Old Seven Mile Bridge with a visiting childhood friend

The road bridge next to Old Seven Mile Bridge (above) was built in 1982

The marine science centre is another big part of the Pigeon Key Foundation work. Currently, the centre is researching Alzheimer’s and cancer medications derived from creatures in the water, as well as carrying out coral restoration and mangrove plantings.

McKinnon has help in running all of this, of course – the other three island residents work on the environmental and educational programmes.

‘We’re a tight-knit group,’ McKinnon says of his select team, who all started out as interns. The longest-serving employee has lived here for 10 years now, and the shortest, three.

‘When I hire people, I’m not just hiring an employee. I’m hiring a neighbour,’ says McKinnon

McKinnon takes a slow and steady approach to hiring people – and who wouldn’t? There’s no escaping that annoying colleague when you’re living next door.

‘When I hire people, I’m not just hiring an employee. I’m hiring a neighbour,’ he says about his recruitment process.

The hints in the questioning seem to land with McKinney, who quickly adds: ‘And I’m not looking to put anyone else on the island.’

Well, that’s our Robinson Crusoe dreams dashed, but at least we can console ourselves with a takeaway.

Source: Read Full Article