I Decided to Move to Turkey From New York. In the Middle of the Pandemic

In February 2020, life was still fairly ordinary, as pre-pandemic living goes. I had been working as a communications associate for a social justice foundation, supporting movements to end gender-based violence around the world. To say it was a dream job wouldn’t be an exaggeration: I worked with some of the most brilliant colleagues who became like family, and for the first time in my life, my values and purpose aligned with my professional ambitions. Only shortly before the new year, I learned my job of four years would be coming to an end. And in early 2020, just as the foundation began restructuring and eliminating roles, coronavirus made its way to New York City. It seemed my sharply-shifting reality would coincide with society’s.

Load Error

Nearly every day, sometimes between Zoom meetings, I watched harrowing reports about the COVID-19 death toll in New York City and how hospitals were barely hanging on. By the time I stopped compulsively watching the news and adapted to the heartbreak of what was happening in the world, I was wrapping up the last weeks with my position and sheltering in my apartment. Just when it felt like the last dominoes had tipped over and despair had fully set in, I’d later see on Instagram stories about George Floyd and Breonna Taylor’s murders (the latter being from my hometown of Louisville), which sparked an unprecedented wave of racial justice protests and a long-overdue nationwide reckoning.

Before the pandemic and protests happened, I knew I wanted to leave the U.S. for a couple of months and escape the chaos. Just a little two-month respite was the plan. I had a secure pot of savings from my job and more than enough to get away for a while. Originally, I wanted to go to Lisbon, my favorite European city, but Portugal’s borders were closed to U.S. nationals. I considered Mexico and somewhere in the Balkans as well, aiming to spend time in a region I had been to before that wasn’t too expensive. I settled on Istanbul, which I hadn’t visited since 2015. Turkey was one of the few countries at the time with no pandemic entry restrictions, and it was pretty easy to travel there thanks to a simple e-visa American visitors can obtain online that lasts for three months.

When I first arrived, I stayed in a studio I found on Airbnb about a six-minute walk from Taksim Square and the connecting pedestrian street, İstiklal Caddesi. As soon as I got to the iconic green and peach statue in the square, I immediately remembered the chaotic flow of yellow taxis and the nonstop, senseless honking, the hustle of döner and kebab shops courting customers, and the chatter of cosmopolitan travelers from the Middle East and Europe, some taking selfies and with shopping bags in tow. Except for this time, everyone was wearing a mask. Restaurants, cafes, and bars were open and bursting at the seams with people, and retail stores were crowded as well, but checking everyone’s temperature upon entering. COVID-19 cases were still somewhat low compared to the United States and after leaving New York City, where activity had virtually died, it felt a little surreal.

Instead of spending my time around Taksim, heading to the old town of Sultanahmet and seeing the Hagia Sophia, or going to the Grand Bazaar and other touristy stops again, I got in touch with my close friend Sinan who told me he would be in Bodrum, a popular beachy peninsula in the south that Turks with summer homes escape to during the warmer months. At the end of August, I accompanied Sinan, who showed me the luscious beaches in the Gümüşlük and Yahşi districts and their ultramarine and endless waters. I vividly remember being in Sinan’s car with the windows down and jamming to Tarkan and other Turkish singers, with sand in my shoes and the Mediterranean sun beaming on my face. My travel desires were feeling nourished, but this was just the beginning.

Even though cases were slowly starting to rise, life was continuing as normal throughout the country, with people mostly just wearing masks indoors but virtually no other restrictions. I soon discovered the “other” parts of Istanbul, such as the up-and-coming Jewish quarter of Balat, and relished in the bohemian and vivacious neighborhoods of Cihangir, Nişantaşı, and Kadıköy on Istanbul’s Anatolian side. I journeyed to two of Turkey’s other large cities, Bursa and Izmir, making friends along the way. Whenever I met people, I always wore a mask and carried around a lot of kolonya, a perfumed sanitizer Turks have been using since the Ottoman empire.

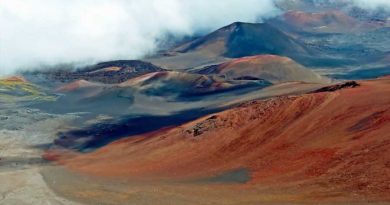

In October, I went to Cappadocia as an early birthday present, knowing my e-visa had less than a month left. As a traveler, I checked off a lot of firsts, including staying in a cave hotel and taking the famed hot air balloon ride across the otherworldly, bouldered landscape. I took a group tour around the region and discovered centuries of Byzantine and early Turkish history, notably in Cappadocia’s underground caves in the Derinkuyu Underground City and the Selime Monastery, a dominating rock-formed complex of chapels, churches, shelters, and secret passages. The abundant hospitality I was always given and the vastness of Turkey, which spans land and time, swept over me.

Back in Istanbul, I continued to live life as a local and began to adopt the city as my second home. I was learning survival Turkish through YouTube and by virtue of having to talk with taxi drivers, store clerks, and strangers on a daily basis. I met people through friends of friends and on dating apps, some of whom would become confidants and even gym buddies. By this time my e-visa only had a couple of weeks left, and my gut told me it was still too soon to return to New York. Would I be able to live in Turkey now—at least part-time—while still having a semblance of my regular life, 6,000 miles away? I knew I wasn’t ready to leave, but neither could I commit to anything truly permanent. So I applied for an ikamet, a short-term residence permit to buy more time.

According to friends I spoke with, applying for the ikamet is a common practice, hence the steady flow of immigrants coming to Istanbul. With time running out, I completed the form online and made sure I had all the necessary requirements. I was staying with one of my friends who served as a guarantor, and also had proof of my income, which were the savings I had after my job ended—more than enough to sustain myself for a year due to the strength of the American dollar. I also obtained Turkish health insurance, a requirement for applying, thanks to the helpful folks at the Istanbul Foreigner’s Office, an indispensable resource for new Istanbulites that I can’t recommend enough. I wasn’t allowed to leave the country during this time and spent months wondering, waiting to get an email or a text message about my application.

I was so dejected to think I might be leaving soon. But my friend Sinan advised me, in a typically Turkish manner, to stay calm. “The best thing that we can do is just to enjoy the time that we have in front of us, and handle the future when it gets here,” he said.

I eventually got a text message to deliver some forms and pay some fees at an official office way out in the suburbs. That day, after muddling through a chaotic queue of applicants and waiting for a couple of hours, I finally got to the registration window and expected to pay my fees and leave and continue waiting another month for more news about the ikamet. But miraculously, after presenting my forms and a copy of my e-visa document, I received a stamped paper stating my ikamet was approved for a one-year stay in Turkey.

Now it’s been over six months since I first landed in Turkey, with a future that continues to write itself. Things are a lot quieter as compared to the summer due to a partial lockdown that began in December which encompasses a nightly weekday curfew and total lockdown on the weekends, with essential travel (like going to the grocery) only being permitted. Tourists are exempt from the lockdown rules, but restaurants are takeaway only and bars and cafes are closed, which has all but killed the city’s boisterous spirit and has forced people to gather in picnics or illegally in their homes. COVID-19 infections have been on the rise but are stabilizing, and the Turkish government has been steadfast in delivering one of the Chinese vaccines to healthcare workers and vulnerable groups.

Thanks to the ikamet, I’m able to return home or travel elsewhere without the worry of having an expired e-visa. With part-time and remote work, a new reality sealed by COVID-19, and the strength of the American dollar to the Turkish lira, I’m dually able to sustain my obligations in New York City while “living” here, with extra time to discover Turkey’s delights.

During downtime, while in Istanbul’s lockdown, I’ve spent my time perfecting my Turkish with a close friend on Zoom and studying with children’s books, learning more and more about Istanbul (a city nearly three times the size of New York) and reflecting on how much my time here has unexpectedly impacted and changed me. Connection to other cultures and self is a huge part of what makes travel so transformative.

I’m truly grateful for the Turkish friends I know and have met along the way, who have welcomed me with their warm arms and never-ending smiles, unequivocally offering me the grandest gestures of help, ranging from helping me with my ikamet application, offering instantaneous translation help when I was in a jam or accompanying me to hospital visits. Part of why I couldn’t imagine leaving yet is quite simply because of them. I’m still sorting out my “life” here, a reality I could never dream of back in February when everything was turned upside down. But willingly letting myself get lost was what I needed to shift my perspective, and reminded me that life doesn’t cease in offering us new and enriching opportunities. And undoubtedly, Turkey is the perfect place to lose oneself.

Source: Read Full Article